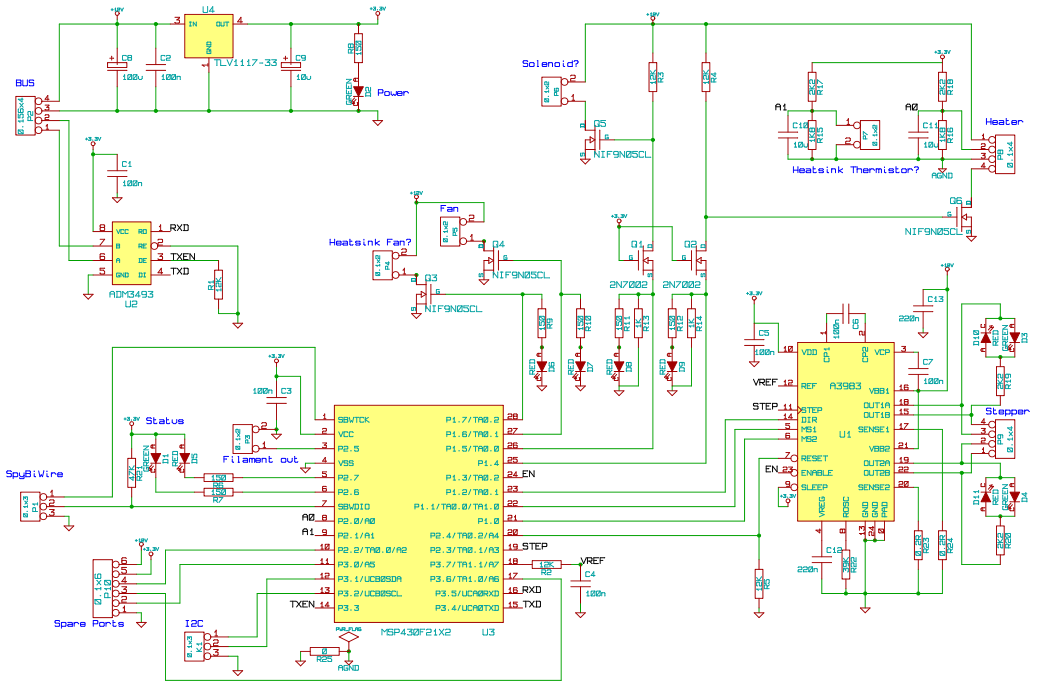

R15, R16, R17 & R18 form the correct potential dividers to give a good approximation to linear temperature response for 10K thermistors, see

for details. For a 100K thermistor they would simply be 10 times bigger. C10 and C11 remove high frequency noise. Probably unnecessary as a little noise actually seems beneficial because it converts bang-bang control to proportional.

The thermistor inputs have their own analogue ground rail, which is only linked to the main ground at one point close to the VSS pin of the MCU. This is done via a zero ohm link, R25, on the schematic. On the PCB this is the smallest footprint available and is shorted by a bit of copper, so no part is actually fitted. The reason for this bodge is to keep the track separate from the ground fill, so that no current from the heater or motors is passing along it. That might cause a small voltage offset that would affect the temperature reading.

R23 and R24 are 1W current sense resistors. I found them to be expensive in the 2512 SMT package. It is actually cheaper to use two 1210 0.5W resistors in parallel, or through hole parts mounted vertically, which take up less board area.

The reference voltage for the chopper is generated by a high frequency PWM output on the micro and smoothed to DC by R2 and C4. That allows software control of the motor current. As I had plenty of spare I/O on the micro I also have software control of the step mode (full, half, quarter or eighth), the enable and the reset pin. R5 ensures the stepper is disabled before the micro is running. As with R1 it ensures the circuit is well behaved before the micro is programmed, or when it is being run under a debugger.

D3, D4, D10 and D11 indicate the state of the stepper outputs, a bit of a luxury really. With SMT parts there is not much point in using bi-colour LEDs. It is cheaper to use back to back red and green next to each other.

I used an

MSP430F2012 micro on my first extruder controller because you get a full development kit including an excellent C compiler, in circuit programming and source level debugging for $20. I think there is also open source support via gcc, but I have not investigated that yet.

For this one I had to move up to an

MSP430F2112 to get a UART for the RS485. As it is the same core with different peripherals I assumed my $20 eZ430 SpyBiWire debugger would still work. Big mistake! It programs OK but it locks up when trying to debug. It also miss-identifies the chip. I have two, and the second one I tried said the firmware needed updating and offered to do it. JUST SAY NO, if you say yes it reprograms the eZ430 and it never talks again. I contacted TI and they have no plans to fix this firmware updating bug so I got an

MSP-FET430UIF debugger for $99. It does JTAG as well as SpyBiWire so I should be able to mend my second eZ430, as it has JTAG test points and I read the security fuse is not blown. I also suspect a new eZ430 may well work as the web page has been updated to show it supports the F21x2 now.

D1 and D5 are red and green status lights. I light the green one to show the processor is running and blink it whenever it receives a command. The red one indicates errors.

P3 is a connector for a filament out switch. I haven't implemented one of those yet as a spool of filament usually lasts many months. It uses an internal pullup resistor to pull it high when the switch is open.

P1 is the SpiBiWire connector for programming and debugging.

Even with extravagant motor control I had three spare I/O lines, so I brought them out to a connector with the supply rails for future expansion.

This is what Kicad predicted the populated board would look like: -

I found 3D models for all the parts on the web but the connectors were a bit of a nightmare. I used Tyco

MTA100 and MTA156 connectors as they seem to be about the cheapest form of wire to board connector. As usual there is an expensive tool to insert the wires, but you can get away with using a pair of needle nosed pliers, or even make a tool as it is only a metal plate with slots in it mounted in a plastic handle. We should be able to RepRap one.

Tyco have STEP and IGES 3D models on their website. Kicad needs VRML, which should have been no problem as CoCreate can import STEP or IGES and export VRML. But Kicad did not like the VRML from CoCreate, it seems it has to come from

Wings3D. Wings can import STL but it does not like the STL from CoCreate or AOI either. In the end I had to do IGES -> CoCreate -> STL -> AOI -> OBJ ->

Wings-> VRML -> Kicad! I coloured the body and pins in Wings.

I got five boards made by

PCB-Pool in 8 working days for €125 including shipping, certainly not the cheapest, especially as it included Irish VAT at 21.5% (VAT is only 15% at the moment in the UK), but I like the web interface, the quality is good and they include a free solder paste stencil.

They also email pictures of the board being made at five different stages, although two of mine went missing. Here it is before the tin plating was added: -

And here it is finished apart from routing the outline: -

Using the stencil is very easy. You trap the board between two L-shaped pieces of PCB material stuck to a flat surface with some masking tape. You then align the stencil over the pads and stick one edge with masking tape. Spread some solder past along the edge that is stuck and then wipe it across the board with a metal squeegee to force it through the holes and leave it exactly level with the surface of the stencil.

You then lift the stencil carefully from the edge that is not taped down.

Notice how the paste for the heat slug on the A3983 is split into four and reduced in area. This is recommended to stop the chip floating on the paste and sliding across the footprint. It was not easy to do in Kicad. It doesn't seem possible to do it in the component footprint, so I had to draw on the stencil layer of the PCB. That means if I use the chip again I will have to do it again. I had the same limitation when expanding the resist layer around the fiducials. These are the two copper circles bottom left and mid right. They are used for optical alignment of pick and place machines.

The next stage is to place all the parts with tweezers. I used 0805 footprints for all the passives, so they were not too fiddly to do by hand. I hope to be able to automate the pasting and placement with HydraRaptor soon.

Then I cooked the board in a cheap electric oven, a

Severin TO 2020 for €45.

I believe you can get these for as little as £15. I expect they give more even heating than using a hotplate, as they heat from above as well as below, but a hotplate has the advantage of taking up a lot less space and probably uses less power. I will be making a heated bed for HydraRaptor, so I might be able to use that.

The temperature profile was controlled by a thermocouple attached to a PID controller that I borrowed from work.

When I have time I will connect one of Zach's thermocouple boards to a spare analogue input on HydraRaptor and plug the oven into the software controlled mains outlet that HydraRaptor has, and then program it as a PID controller. Not another head, but certainly another manufacturing capability. I will also try putting extruded objects through a heat cycle in the oven while they are still attached to the base. It should release the stress so they don't warp further when removed.

This was the finished result after hand soldering the connectors: -

U2 is not fitted because I got the footprint wrong, doh! I can bodge one on when I need RS485. There are two construction faults on this picture, can you spot them?

The reflow was not perfect. The big capacitor did not flow at all. The temperature needs to be a bit higher, or perhaps the warm-up a bit slower. There were solder bridges on the TSSOP chips. That was because you are supposed to shrink the stencil apertures by an amount related to the stencil thickness to get the correct amount of paste. Normally the stencil manufacturer will do that for you but PCB-Pool do not offer it on their free stencils, presumably because they are shared with other designs. Unfortunately Kicad only seems to be able to make them 1:1 with the pads. It is open source, and written in C++, which I know well, so I could have a go at adding that facility if I had the time.

I have tested the board and used it to control one of my experimental extruders, more details tomorrow. The only thing wrong with it apart from the foorprint error is that the A3983 gets too hot to deliver its full rated current of 2A. 1A is no problem, which should be plenty for the extruder designs I have in mind.

The back of the board is nearly all copper to give a good heatsink but at 2A per coil the chip will dissipate 2 × 2A

2 × (0.3Ω + 0.3Ω) = 4.8W. The datasheet recommends a 4 layer board with 2oz copper on the outer layers. I am not sure what the extra cost of 2oz is. I will investigate the heat distribution in more detail at some point.