Printed Parts

Unlike when I printed two sets of Darwin parts, printing the parts was the easy bit. This was due to three breakthroughs I had at the beginning of the year: -- The heated Kapton bed removed the need for rafts, which not only take a significant time to print, but also can take a lot of manual work to remove.

- The extruder fast reverse got rid of all the strings, which also took a long time to clean up, especially from inside the Darwin corner blocks.

- The "no compromise" extruder is so reliable that I have the confidence to do multi-part, layer by layer builds, which gets a lot more on the table, allowing longer unattended operation.

I printed the parts with 0.4mm or 0.375mm filament and with 25% infill. For the larger parts I used two outlines for strength. Since the large parts don't need fine detail, I think printing them with 0.5mm filament and one outline would be quicker, but that would need a bigger nozzle.

The weight of the parts, not including the extruder, was only 730g. I printed the outlines at 16mm/s and the infill at 32mm/s, so it's hard to say the total time. Assuming an average speed of 24mm/s at 0.4mm diameter gives about 3 mm3/s. That would put the total time at about 65 hours. I did it as a background task over a few weeks. A lot of the parts were printed as experiments with heated beds.

Rods

I took me an evening to cut all the rods. The method I used was to nail a stop to my workbench to line up the rod against a metre rule.

I then lined a piece of masking tape up with the correct measurement and wrapped it round the rod to mark the place to cut. I also wrote the name of the rod on the tape to make it easy to identify later.

A Black & Decker workmate makes an ideal vice to hold the rods while sawing. I rotate the studding until the thread lines up with the edge of the masking tape. That guides the saw to start in exactly the right place.

I used BZP for all the studding except the z-leadscrews, for which I used A2 stainless steel because it is smoother and generally straighter. I bought the rods from Farnell and even the BZP studding was very straight, a lot better than the stuff you get in B&Q. I also used A2 for all the bars.

It was very hard work sawing the A2 until I switched to a new blade and used Trefolex cutting compound. I am not sure which made the most difference, but I could then cut the A2 much easier than I had been previously cutting the BZP. I wish I had done that earlier, it would have saved a few hours.

Thick Sheets

The thick sheet parts are not really suitable for making by hand, particularly the squashed frog. They have lots of slots, which are hard to make without a milling machine or a laser cutter, etc.

I am not sure exactly what the hole in the bed and the purge plate are for, so I made the bed a simple rectangle with four holes. I am using my own electronics, so I made the two circuit board plates to suite. I simply cut rectangles and I marked the holes and drilled them in the right place, so no need for slots. That just left the squashed frog.

I made a much simpler design with drill centres on it. There is no need for the bulging legs and sloping shoulders. I think they must be just to make it look more like a frog. Fine if you you are CNCing it, but a PITA if you have to make it by hand. Also the holes for the opto tab and the purge plate are mirrored for no apparent reason, so I made it chiral.

This just starts as a rectangle with some holes in it. Then the large slots are made with a saw thin enough to turn in the holes. The outer holes that mount the bearings can be round because they are in a a fixed place, dictated by the holes in the bed. The inner holes need to be slots because the bearings are adjustable. I just left them off the template and marked them with the bearings adjusted and in place.

I made the sheets from 3mm Dibond, which is below the recommended thickness, but seems stiff enough. It is also light weight and very easy to machine.

Thin Sheet

I didn't have any optos, so I used micro switches for my end stops, hence didn't need any thin sheet parts. I simply attached them to the bars of each axis with P-clips. A little RepRapped bracket would be better but I was building this in a hurry, so had gone into bodging mode at this point!

They seem to have sufficient repeatability and certainly will when I replace the electronics with my new design, which will know the motor phase, reducing the uncertainty by a factor of 32. It is the same switch that I have used on the z-axis of HydraRaptor, which has proven totally reliable. They seem to be this one from RS, not cheap.

Belts

These were easy enough to split but, because the reinforcing wires run in a spiral, the blade tends to follow one for a while before managing to cut through it. That leaves a ragged edge with a bit of wire sticking out.I didn't understand the rationale for slackening the belts until you just don't see backlash when moving one motor detent. I am microstepping anyway, so a motor detent is not significant. I made my belts good and tight.

Snags

I had a few snags with the mechanical assembly: -The x-axis spacers are too short. The STL files are 5mm shorter than the parts in the STEP assembly. That caused the motor to clash with the nuts on the 360 bearing.

The 180 bearing at the other end was about 10mm from where it should be.

A simple fix was to slide the axis along leaving a 10mm gap to the spacer, the only problem remaining is that the spacers rattle at certain step rates.

The STEP model shows this gap should be only 5mm, but I have been unable to find the discrepancy. My rods and inspection distances are correct and the ends of the rods are flush with the clamps, as they are in the model.

The bed springs seemed to be too long to compress to the length of the bed-height-spacer-31mm_1off, which is not actually 31mm, but 29mm, so I don't know what gives there, I just spaced them a bit higher.

The bolts in the z-bar clamps are too long to allow the bearing to be inserted. I replaced them with shorter ones.

Similarly the bolts in the x-carriage get in the way of the extruder I fitted.

The J3 jigged distance did not seem correct. The distance between the y-bars is set by the J2 distance and the 3 nut spacers.

Extruder

I used Wade's extruder design as I didn't have time to adapt any of my own.

The gears work well, with very little backlash, but the small one has some movement on the motor shaft. It is just a press fit with a flat on the shaft. I need to redesign it with a captive nut and grub screw.

I didn't have a suitable M8 shoulder bolt so I made one from brass by attaching a nut with a pin through it.

I hobbed it with an M3.5 tap. I haven't measured the grip, but I get the impression it is not as high as Wade gets, I am not sure why.

For the bottom half of the extruder I used some parts that Brian was looking for volunteers to test for him.

The insulator is made from PEEK with a PTFE liner. The idea being to get the strength of the PEEK and the slipperiness of the PTFE. It seems to work well with PLA, which is all I have run through it so far.

The barrel is long because it is designed to take nichrome, but I just screwed it into a block of aluminium with a vitreous enamel resistor in it.

This was left over from a previous experiment. I have now moved onto a smaller resistor size, so this block could be smaller. The barrel could be a lot shorter with this arrangement and that would give less ooze and less viscous resistance.

The extruder works well with PLA. The main problem with it is that it mounts at right angles to the x-axis, so the motor severely restricts the maximum height of the z-axis. Another issue is that to remove it you have to remove the motor to get at the bolts. To remove the motor you have to remove the big pulley to get at the motor's bolts, to do that you have to remove the pinch wheel assembly. I.e. to remove the extruder you have to completely disassemble it!

Electronics

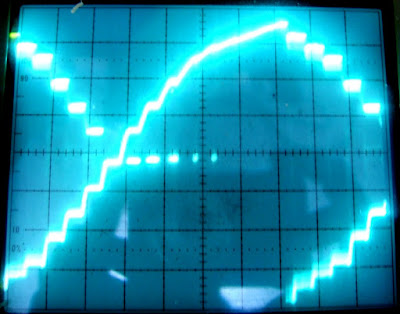

To get up and running quickly I used the same electronics that I use on HydraRaptor. The only difference being that I used MakerBot V3 stepper drivers. These use the A3977 chip and give x8 microstepping. That gives an axis resolution of 0.025mm, but more importantly gives nice smooth running.When the weather was exceptionally dry I found they are very sensitive to static. A discharge to any part of the machine would cause the A3977 to shut down its outputs and draw enough current from the 5V rail to cause the 100mA regulator to current limit. The red LED on the power rail goes dim. Powering off and on again fixes it and there doesn't seem to be lasting damage. I suspect that might not be the case if the 5V rail was not current limited. Apparently the only way to fix it is to add external Schottky diodes. That is very disappointing as one of the nice features of the chip is that it is supposed not to need them. I will investigate further to see if all eight diodes are needed before making my own board.

Firmware

I used the same firmware as HydraRaptor. I just added some compile time conditionals to cope with two pin outs and a different IP and MAC address for each machine. I also had to change from 16bit to 32 bit positional commands because the axes are bigger.Software

I used the same Python software as HydraRaptor but I had to re-factor it quite a lot to support both machines. I added a class to represent the Cartesian bot which holds the axis resolution, direction, maximum speed and acceleration plus the IP address. I also added a class to represent the extruder controller as I have calibration values unique to each board. I already had classes to represent thermistors and extruders.I can run both machines at the same time from one PC and, because I only use the Skeinforge output for the toolpath, I can use the same sliced files for either machine. This is despite the fact that they run at different speeds and are loaded with different plastic.

Results

So here is the finished machine: -

And here is a video showing it being tested: -

I am running the X & Y motors at about 0.75A and Z at about 1A. I have set the maximum XY speed to 100mm/s, but I think it could go a lot faster. Z only goes at about 5mm/s because not only is it a threaded rod drive, but it is geared down by the belt and pulleys!

I haven't printed a lot yet, but so far the results look as good as they do from HydraRaptor. The next thing to do is add a heated bed and try ABS.